On the sublime, or the arduous task of saving beauty

João Paupério & Maria Rebelo, Ark, #46 Sublime, 2023 Link

The pursuit of the sublime aligns with the social function of the Architect, because the desire for the sublime is not the Architect's invention.

As a philosophical category, the sublime has an ancient heritage with meanings that have evolved throughout history. From its etymological root, “sublimis” (sub “up to” + limis “limit”), one can infer the common condition of referring to an apex, that is, a radical form of aesthetic experience. In truth, the desire to understand it as such has accompanied us at least since the times of Plato’s Greece or the Ancient Rome of Pseudo-Longinus. However, as the philosopher Byung-Chul Han explains, the separation between a negativity associated with the sublime and a positivity associated with beauty is much more recent. [1] In modern times, this distance was established by Burke and, alongside him, Kant. Associated to how the inexpressible violence and hostility of nature, for instance, awakens in us other forms of sensitivity associated with a fascination for the incomprehensible, to terror in the face of the unknown, or the overwhelming feeling towards what is so vast that it simultaneously represses and elevates subjects in their capacity to evoke the unintelligibility of the infinite itself. Before this, the sublime was an intrinsic condition of beauty which, in turn, was much less exclusively associated with harmony and pleasure and much more with shock. In other words, the negativity of the sublime and the positivity of beauty went hand in hand.

A few years ago, when we reflected on the Archaic and the Sublime, our perspective was based on a chapter of the same name from a book written by Jacques Lucan. For him, the condition of the sublime is understood primarily in the relationship that the subject establishes with “infinity,” that is, with a feeling associated with the difficulty (if not impossibility) of fully comprehending the scale of Nature. Therefore, it is an experience associated with a certain condition of “grandeur.” As he wrote, “the sublime cannot be produced from (small) parts that are assembled or composed. The sublime is produced by a building that is perceived as a whole, immediately apprehensible, and that is not comprehensible or interpretable according to conventional criteria.” [2] Drawing from Burke, Lucan presents the Stonehenge as a concrete example. Despite containing nothing particularly admirable from a compositional or ornamental standpoint, it becomes sublime due to the size of the stones and the difficulty in imagining how they were assembled.

From our perspective, however, what is particularly interesting in his text is the concept of Nature not being limited to something external to the human being, but also to what the human himself constructs as a “natural” endeavour: the city. The sublime does not only pertain to the untouched majesty of the Alps, to take a classic example from English literature, as well as to the very complex and conflictual ecosystem that contemporary cities have become. This is why some of the main references Lucan used to refer to the sublime condition of certain contemporary architectures are works by OMA, the office of Rem Koolhaas, who is also one of the most prolific theorists on the architecture of the metropolis. These projects, to use the latter’s own words, focus on what was once called the city and which today is characterised, among other things, by its “bigness” and “generic” nature.

If, as Lucan suggests, the sublime is a product of what surpasses our familiar understanding or knowledge, then the rapid and often chaotic development that urban spaces have undergone in recent decades, over the globalization of capitalistic economies, this has surely led the aesthetic experience of the city into that sphere. While the preserved (but often uninhabited) centres of some European cities belong to the conventional “order of the beautiful,” their peripheries, which continue to grow and now consume the vast majority of urban space, can at best be said to belong to the “order of the sublime.” [4] As others have previously suggested, they are to some extent beyond the “beautiful” and the “ugly.” [5]

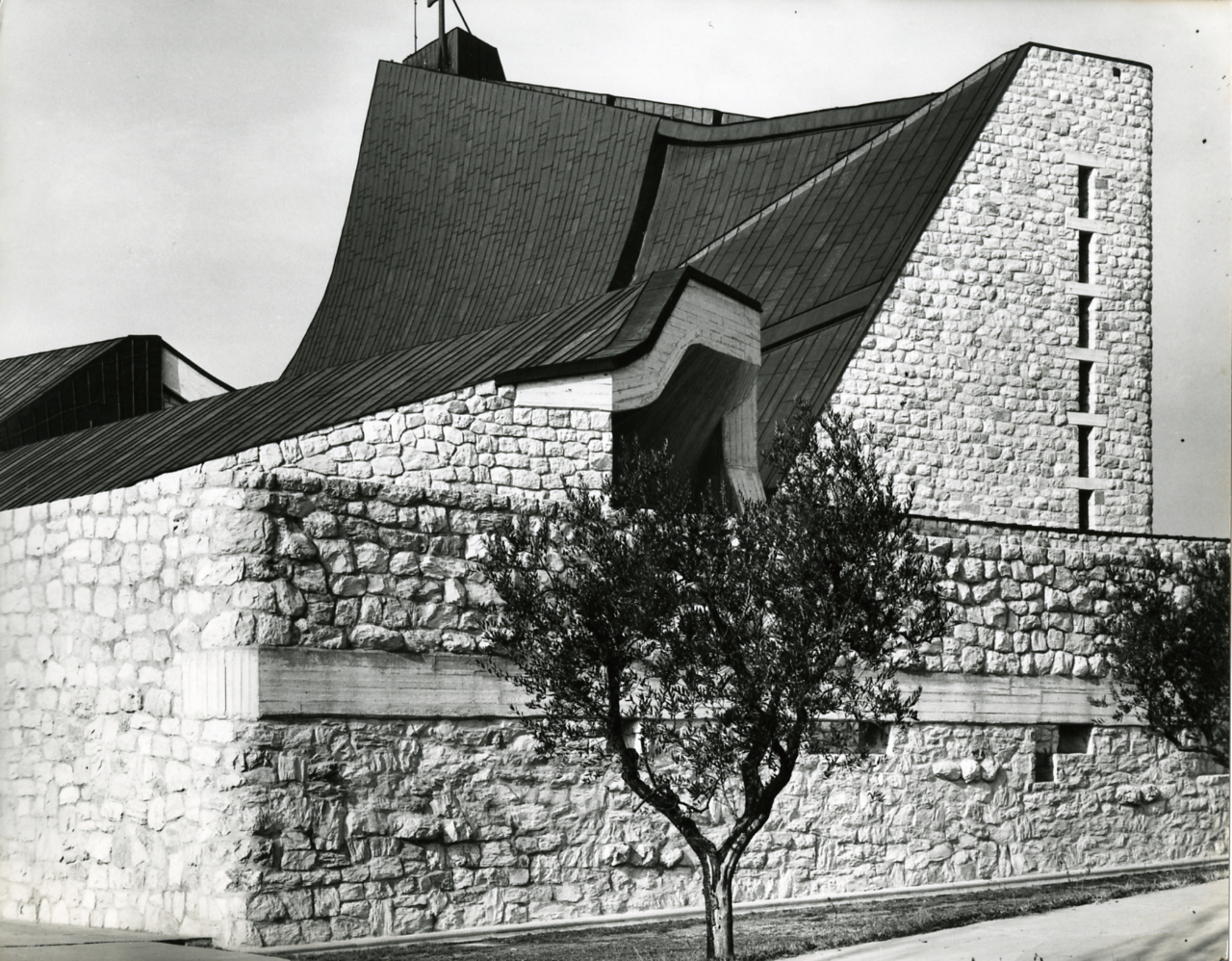

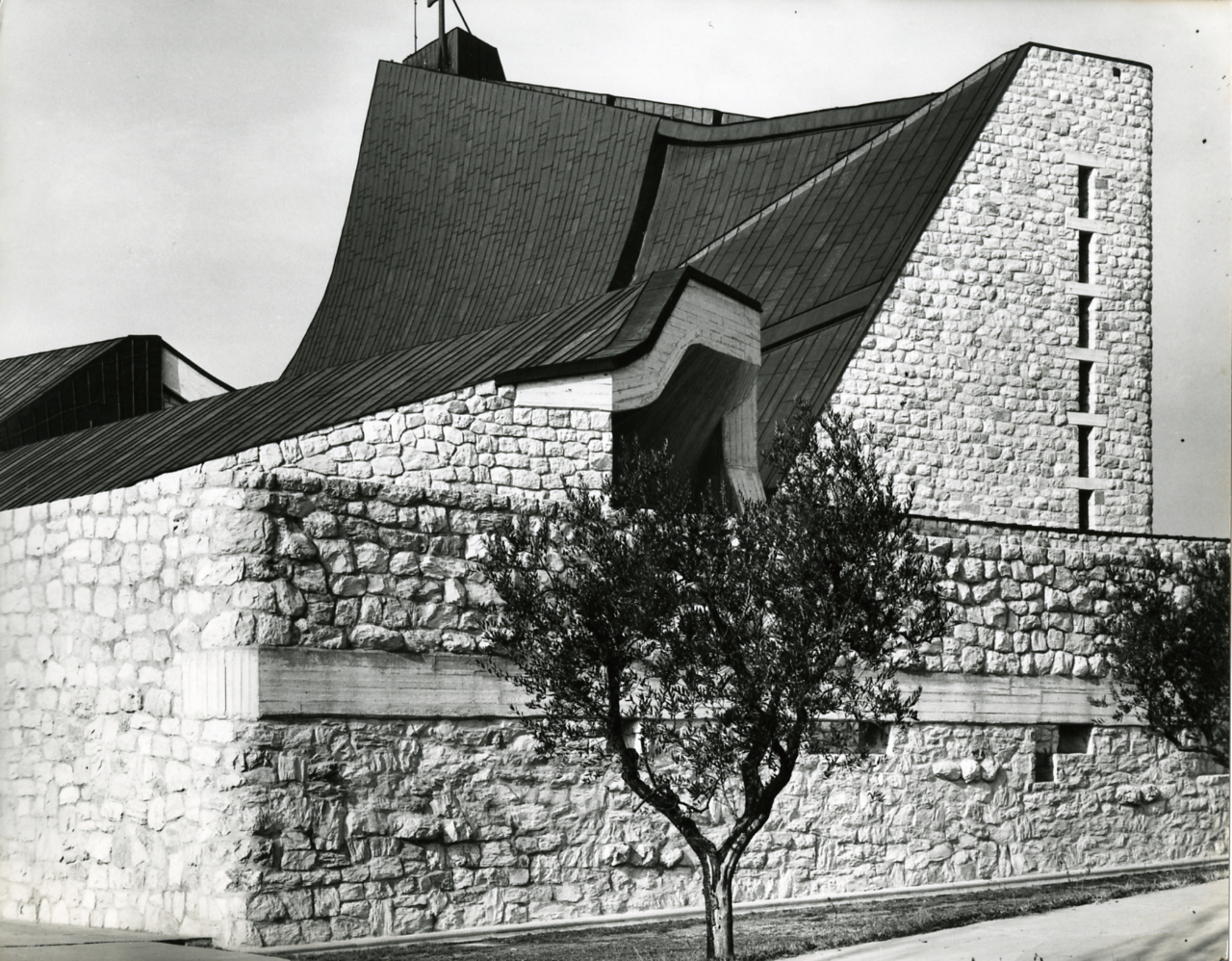

In this issue of Ark all the projects presented deal, in one way or another, with the incomprehensible. From Viganò’s Istituto Marchiondi Spagliardi, which proposed a “school of life” instead of a juvenile reformatory to address the traumas inherited from the war to Carlo De Carli’s Church of S. Ildefonso, which aimed to grapple with the mystery of faith in a time when it was beginning to wane; to Molteni’s warehouse, tasked to materialise the ineffable nature of automated work, all the more so having to communicate this effort at the speed of the nearby motorway. In all of these, the systematic and serial character of their architectures is certainly a response to this problem. They seem to withdraw from the domain of composition towards the almost infinite scale of today’s cities. Or else, as the Smithsons wrote (and it seems no coincidence that there’s an inclination towards Brutalism in the editorial selection), in order to find a strategy “to face a mass-production society, extracting a rough poetry from the confused and powerful forces at play in it.” [6] Although not feature in this issue, we cannot help but also think of the Church of San Giovanni dell’Autostrada del Sole, designed by Giovanni Michelucci.

In his book, Byung-Chul Han insisted that the “beautiful” and the “sublime” have the same origin, arguing for the urgency of undoing the separation between the two. On “beauty,” Siza argued that the notion of the Beautiful is always in crisis and that the “refusal of consensual beauty is the threshold of authentic beauty (much of what appears initially as not beautiful or rough).” [7] For us, facing the sublime condition of the contemporary city means not shying away from the responsibility of confronting all its contradictions, as well as the possibility of regarding architecture as a tool to make them a bit more intelligible. To better understand the place and role we play in the world today. To face the contemporary city as it exists and starting from there to transform it, from the infinitely small to the infinitely large.

As for beauty in architecture, it might be worth remembering that from a linguistic point of view the distance between the sublime and the subliminal is shorter than we usually acknowledge.