Brief notes on a theory of practice for the ordinary

João Paupério & Maria Rebelo, Punkto, #38, 2023 Link

Culture is ordinary: that is where we must start.

Who would be surprised that the luxury of the poor lacks invention, if it is a loan taken from another loan? The scene that the worker appropriates today is the one from which they have been excluded until now.

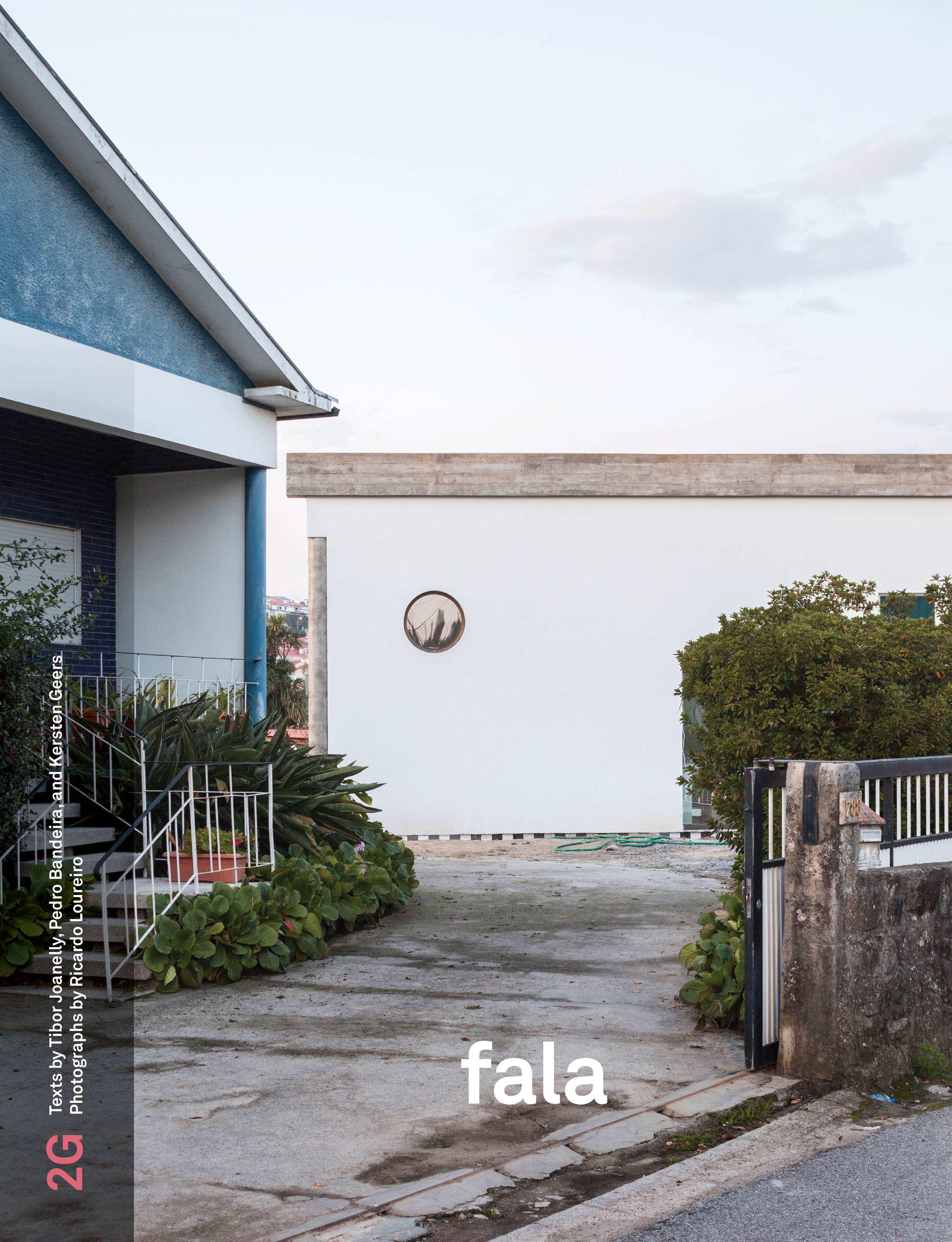

Despite the proliferation of images that characterizes the work of fala atelier, through which they have become so recognized and recognisable, there is one that in our view better mirrors what might be the sense of their architectural project as a whole. We refer to the photograph chosen for the cover of a monographic issues in the 2G series (Walther König, 2019) dedicated to their work. In this image, one can see a house built in Famalicão according to project 072, which according to the authors “feels like a house” (or as we shall see later “looks like a house”) and thus seeks to aim for a kind of “agreeable complexity” [1]. What immediately captures our attention in this image is the fact that in the foreground we find not the project itself, relegated to the background, but another house. A house that in its apparent banality looks indistinguishable from so many others found in peripheral areas or along that “Road street” [2] stretching across Portugal.

That an architectural work is portrayed in face of its context, whether close or further away, is not in itself a remarkable feat. Yet, it is much less common to choose for the cover of a monograph a viewpoint where the depicted work does not stand out as a figure, but is instead relegated to the background. Especially when what surrounds it does not depict a precisely idyllic or extraordinary scenario, a “landscape” to be contemplated and crowned by the presence of yet another “object” [3].

A keen eye and a brief comparative analysis of the two houses, however, swiftly reveals what one imagines to have been the photographer’s intent when he decided to highlight the first house (despite it having already been there and, by all accounts, having remained untouched by the intervention of fala atelier). In fact, consciously or unconsciously, this front house seems to establish the compositional matrix that defined the image of project 072. Tripartite between a stone podium, a column which frees itself from the wall (with a sensitivity of someone familiar with the craftsmanship of the Roman temple or the Palladian portico) and an architrave that supports a prominent pediment, this small house of popular character built with modest construction techniques and materials seems, nevertheless, to claim the dignity and artistic pretension proper to a classical temple.

That this is the case is not surprising. Especially if we consider true what Michel Verret [4] wrote about the constitution of architecture as an autonomous professional and theoretical field, that is, of an architecture with architects. An architecture “with pedigree” as opposed to, let’s say, the “architecture without architects” that interested Rudofsky [5], and whose shared knowledge was mainly based on two principles that we should mention here without having the time to delve into: making do and making as. Although in different forms and with different resources, this condition extended from vernacular architecture to other forms of popular architecture, including some of the more contemporary ones such as those referred to in this text.

In this regard, it is also important to reflect on the contemporary definition of being local in the space-time of a globalization that “explodes, layer by layer, the dreamlike envelopes of collective life, rooted, closed and self-centered,” dragging “cities open to commerce and even, ultimately, introverted villages, into the space of circulation that reduces all local particularities to two common denominators – money and geometry.” [6]

After all, if in the past the stone with which houses and temples were built would come from nearby or from the very ground on which constructions were erected, today (the stone as well as its myriad of reproductions) can be purchased at the nearest DIY store but has most likely benn produced or extracted in the antipodes of where we are placed.

As we wrote before, regarding the constitution of architecture as an autonomous disciplinary field, the French philosopher and sociologist reminds us that “the working class had no possibility of doing it on their own: excluded simultaneously from the field of theory, from the field of architectural professionalization, and from the formalization practices that concern them, they remained within the practical horizon of the inhabitant builder or the builder inhabitant.” Precisely for this reason, “they can hardly desire anything other than [the luxury] they have seen: that, therefore, of the classes whose distance remained closest to them, that of the petite bourgeoisie,” or rather, the taste “that the petite bourgeoisie had previously copied from the salons of the bourgeoisie, these themselves partially transcribed from noble salons, in a cascade of deformations inflicted from tier to tier on the original model.” Reacting to the smoothness of the factory and the coldness of the industrial environment, ornamentation acquired a redoubled importance in this possible appropriation movement, as it operated as a form of “revenge against the poverty and deprivation” suffered by the workers. [7]

In essence, and so to speak, the economy of beauty became for the working class a political form of subversion claimed (and often DIY-ed) with their own hands.

On the other hand, Verret also explains that there is a reason why this popular ornamentation is of such poor quality. Indeed, “how could it be otherwise if one of the functions of industry is precisely to mask – the consumer is not the master of supply – the lack of quality in the product: carpets instead of parquet, wallpaper to hide cracks, designed motifs to hide the flaw in the plate”? The worker, he concludes, “is too close to the technique to ignore it,” but is also “too close to poverty to refuse the defect” and “too far from wealth, and from satiety, to access or even conceive the supreme luxury of simplicity that the rich, tired of all ornaments because they have had them all, can today afford in flawless products, but of very high value, and therefore out of the ordinary, from the craftsmanship of art or the luxury industry.” [8]

In summary, those who were historically excluded from Architecture were also forced to reproduce, with only the means at their disposal, what seemed to them legitimate as such.

As a material asset exposed to the perception of others, Pierre Bourdieu suggested, the house expresses or reveals the social status of its owners, their ‘resources,’ but also their tastes, more decisively than other assets. Therefore, it is crucial to understand “the structure of distribution of economic dispositions and, more precisely, of tastes in housing matters,” “not forgetting to establish through a historical analysis the social conditions of the production of this particular field and the dispositions that find the possibility of materializing more or less completely.” [9]

Even though this classification might be open to debate, it is the heirs of these “popular classes” once excluded from the commissioning of architecture and now partially transformed into middle classes pushed towards (increasingly difficult) access to credit as a way to individually solve their housing problem, [10] who form an important base of commissions not only for fala atelier but for many others of their generation. In other words, classes for whom the conquest of the right to housing—under the best scenarios accompanied by the right to the city as well as to architecture—has been replaced by the “right to buy” [11] or build a dwelling by their own, probably far from what might remains of the old “city”. Most likely, regarding architecture not so much as a right or a life benefit, but as a bureaucratic process, a legal responsibility and in the best case scenario as a form of commodity valorisation.

Fala themselves have written that “the vast majority of [their] clients are like the vast majority of people,” meaning they “do not have a specific interest in architecture, sometimes demonstrating a radical skepticism towards the figure of the architect.” They contact them, they add, “because they need paperwork signed and often arrive with a catalog of houses, pointing to the one they desire”; or whose identity, one should add, they constructed fragment by fragment with the help of random images collected on Pinterest or another equivalent social network. These images are assumed to be an expression of their uniqueness, but more often than not they are simply a direct translation of the fashions and trends that are periodically “offered” en masse to consumers by the market. Generic images, of course; yet they still demonstrate that a popular desire to access the privileged domain of aesthetics lives on.

In this context, incorporating the expressive qualities of an aesthetics of mistakes which seems increasingly inevitable in a context of deteriorating working conditions, and dwelling between an immense field of disciplinary references and the close sensitivity of a popular subjectivity, fala’s architecture seems to find its rightful place to exist despite the limited, and often precarious, objective and subjective conditions in which it is forced to operate.

It is no coincidence that in their works, much like in the “worker’s space”, whenever an ornament or a stylized formal maneuver stands out, there is a strong likelihood that these correspond to an effort to circumvent or distract from an unexpected mishap or a flaw in the project’s execution. In a curious reversal of the project’s order, the plastic charge that characterized the collages fala atelier used so much at the beginning of their career (as a strategy to compensate for the lack of built work and compete with the visual hegemony of images flooding the internet) now appears to result from a refined project strategy to deal with the current conditions of architectural production in Portugal.

Ultimately, this is one of the thoughts that the cover of the 2G magazine carries within it: if we reverse the direction that determined the “deformations inflicted from tier to tier on the original model”, the approach developed by fala atelier challenges the hierarchy that has been established throughout history between the canons of erudite art on one side and the “naivety” [12] of folk art on the other. Or, put another way, it questions the distance that has been established between what typically stays on the outside and what is considered to be within the disciplinary field of architecture.

Whether one appreciates or not the final appearance of their architecture, whether this was their original intention or not, what this reversal of direction enables one to do is primarily to rethink how we perceive and reflect upon those ordinary architectures of popular expression. Setting aside disdain and re-learning from this “local economy” (to use their own expression): not so much to elaborate a renewed theory of popular architecture, but perhaps to entertain the possibility of a popular theory of architecture.

While it is true on one hand that a characteristic of popular architecture was once its vernacular condition—meaning its belonging and sharing of culture and local materialities—and on the other hand, that culture always exists in relation to an underlying system of production, it is also true that culture is today largely globalized and a substantial portion of the materials we currently use come from all over the world, through international supply chains.

Certainly, if we consider that (1) architecture is an art, and that (2) true art is always a process aimed at suspending the current state of affairs in order to be able to establish new truths [13], then, as Pedro Bismarck aptly explained [14], this popular theory inevitably refers to a people that is yet (and perhaps always will) to be invented. Nonetheless, it seems also evident that this missing people will not be invented out of nothingness, nor will it emerge from ideas formulated out of any holy mind, but will instead emerge from the subjective materiality of that which already exists among us. If popular culture is nowadays produced commercially and according to profit-oriented logics (think, for example, of the quantity of “synthetic” materials imitating higher-quality raw materials), it still contains the seeds of desires and aspirations that remain legitimate [15] and whose political potency will always depend on what is done with them, as well as with the DIY stores where we find those “local” products. After all, the Portuguese marble that characterizes fala atelier’s architecture may well be understood within academic circles as an erudite reference to the Renaissance palazzos (or to the image of those palazzo); but considering the origins of its founders, it is hard to argue that this subjectivity has not been primarily shaped, over decades, by the aesthetic condition and by the specific ecology of those popular peripheries where they grew up. It is from these places that an increasing number of newly graduated architects are now emerging, prompting an urgent need to rethink not only the past but especially the present and future of cities, society, and everything architectural that lies in-between.