Studio house

Valongo, 2015–22

Team

João Paupério

Maria Rebelo

Photography

Francisco Ascensão

Luca Bosco

Studio house

Valongo, 2015–22

There are no extravagant finishes, built-in wardrobes or walk-in closets.

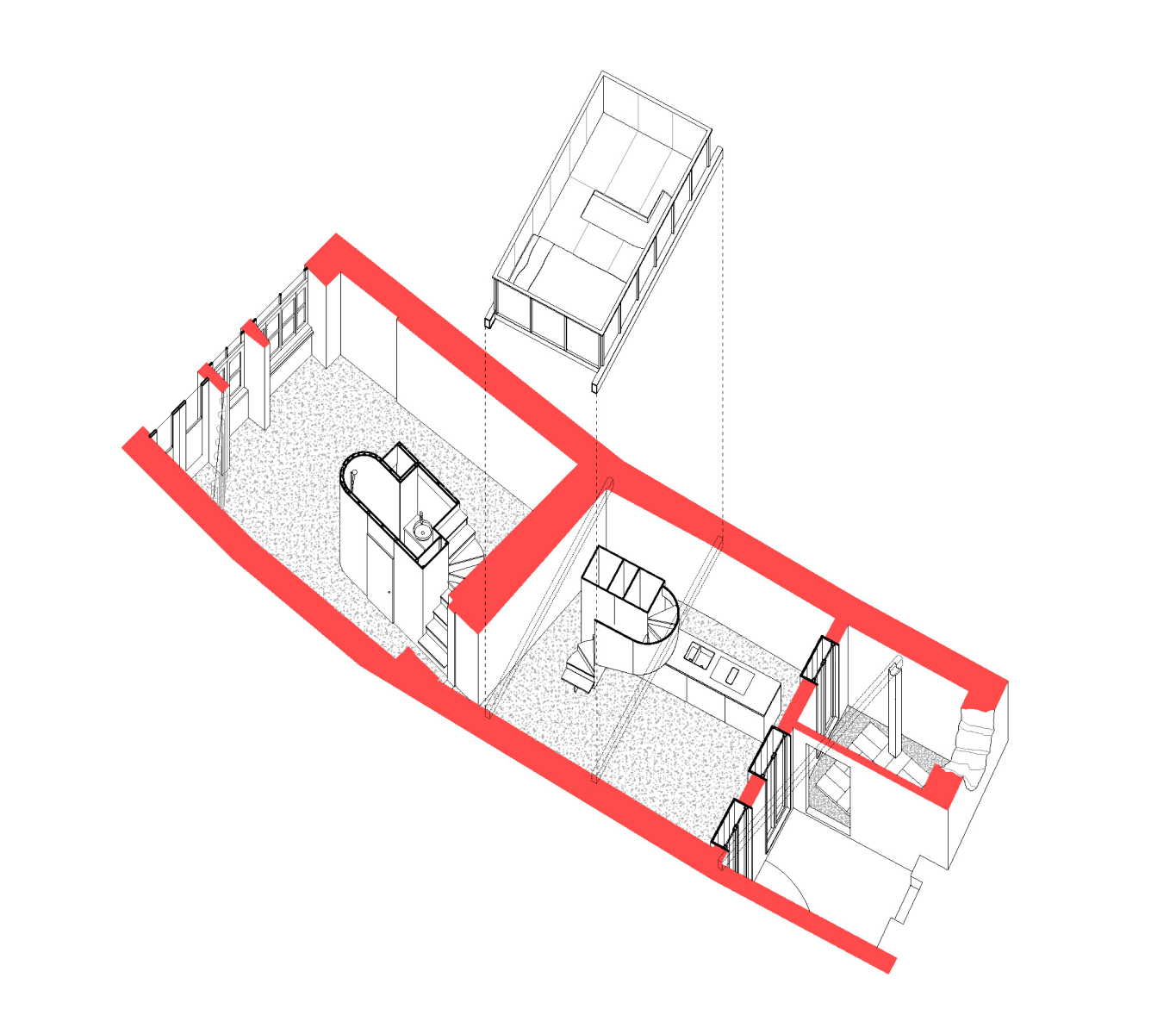

In their manifesto “il fera beau demain” (1995), Anne Lacaton & Jean-Philippe Vassal issued a warning to those who design and build today, writing: “we deprive ourselves of extraordinary architecture in the name of a little bourgeois comfort.” Based on (or against) this assumption, the rehabilitation of this two-century-old house aims for the opposite: an anti-aspirational aesthetic. Inside, there are no master bedrooms or suites. There are no extravagant finishes, built-in wardrobes, and much less ‘walk-in closets.’ The shapes of its spaces do not follow predetermined functions, as the goal is for neither labels nor conventional domestic protocols to be respected within this house.

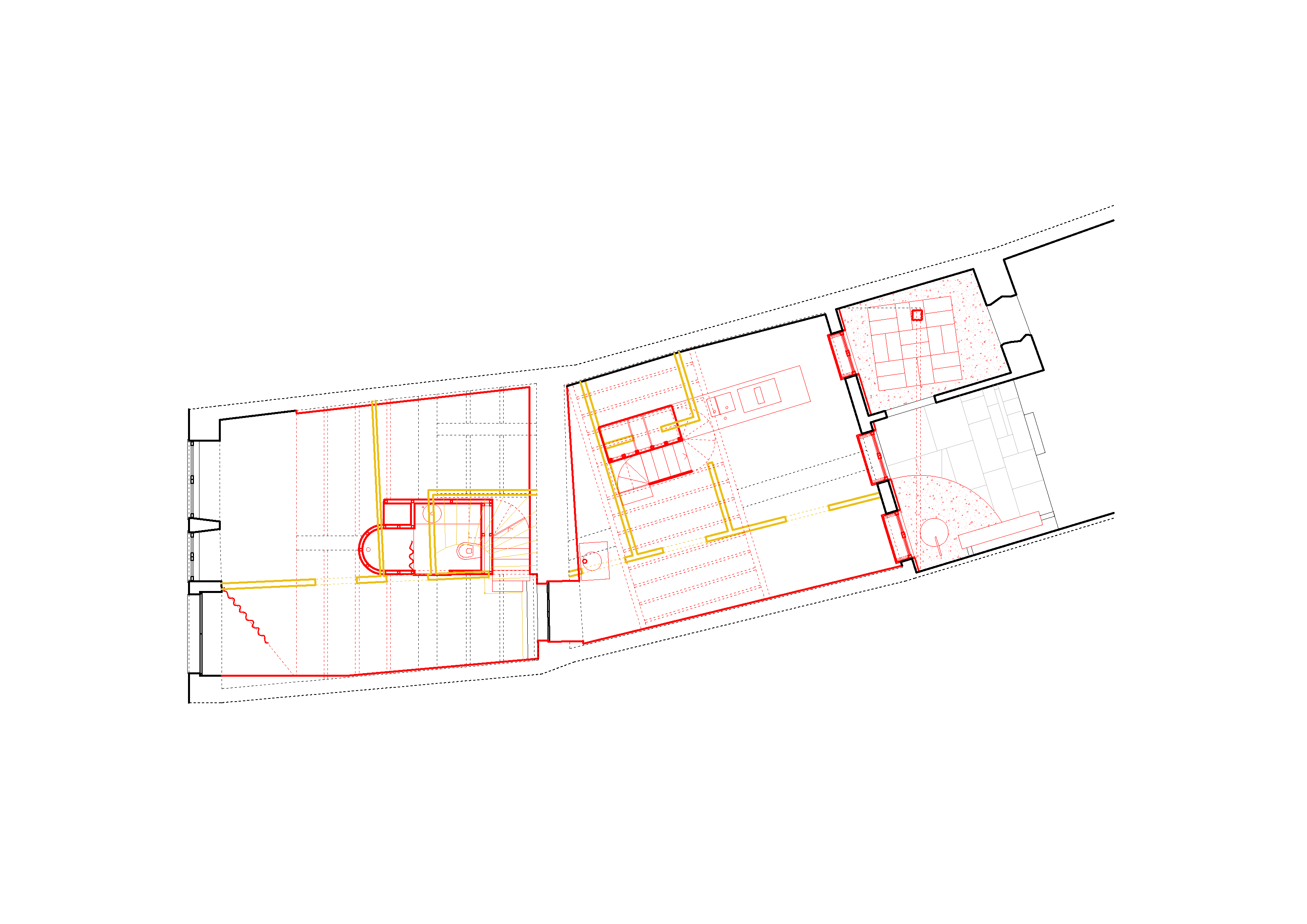

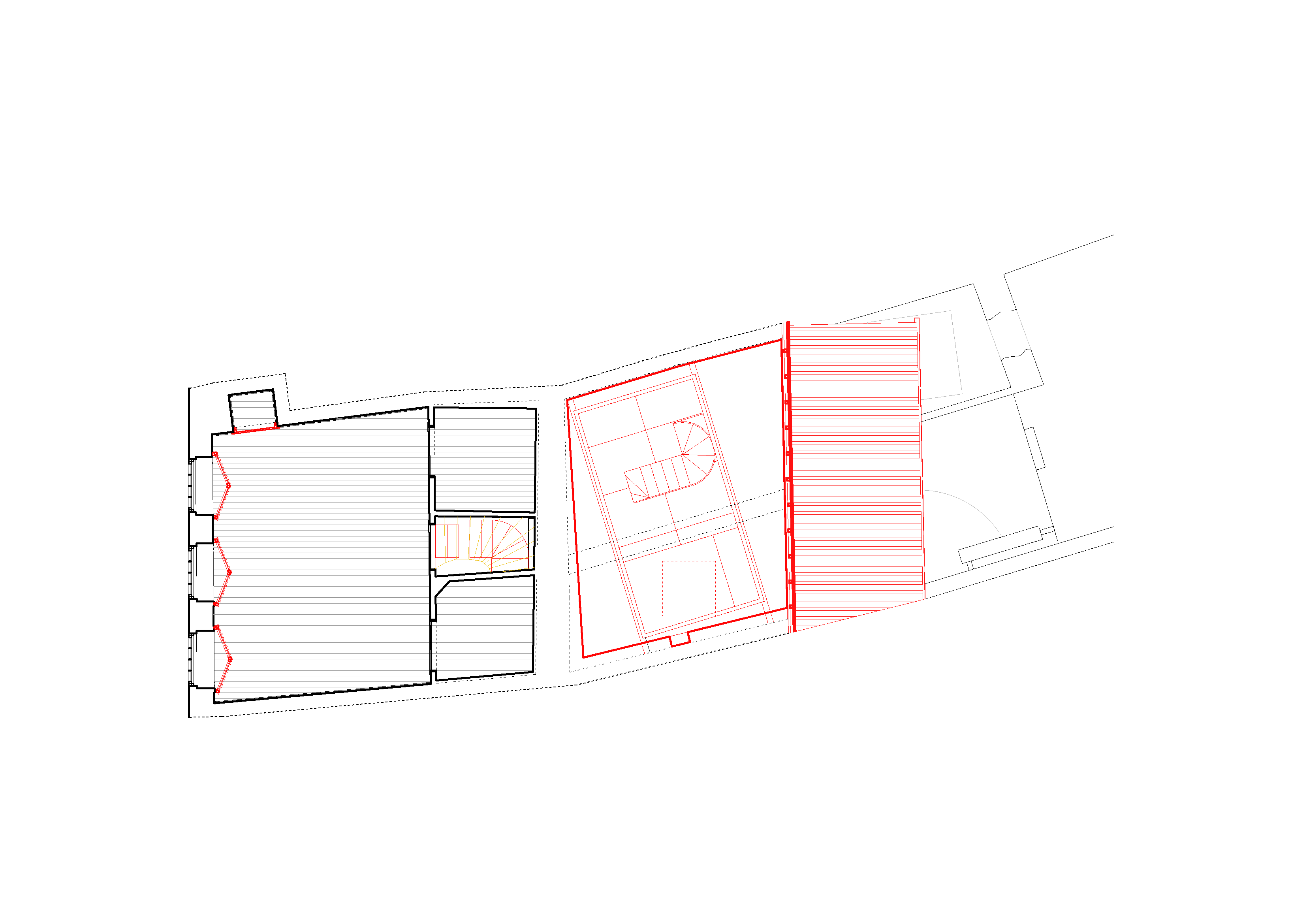

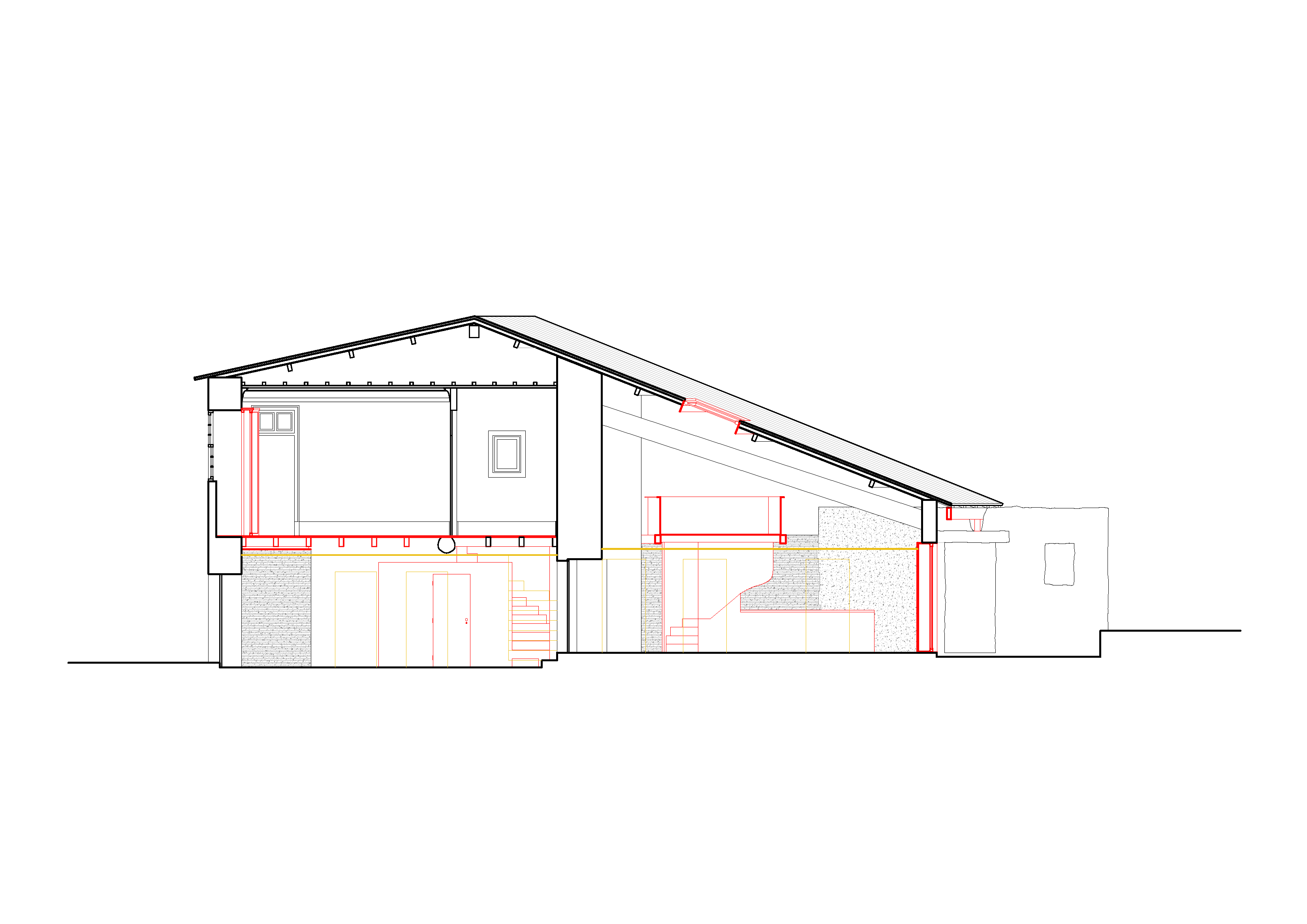

Outside, one does not find an idyllic garden but rather a productive garden, shared with a landless farmer. Inside, there is no strict division of labor: the architecture studio, the house, and the garden coexist without necessarily overlapping, creating contradictions that seek to resolve any antagonisms. The building that once stood here was stripped of what was superfluous, and only what is considered strictly fundamental was rebuilt: two habitable sculptures containing the essential infrastructure for basic needs — a kitchen and a bathroom — and a series of useless spaces; “extra-ordinary” because they are impossible to name. Apart from these, only a mezzanine was added, for practical reasons of intimacy. These new volumes were built with pinewood, marine plywood, and water-resistant MDF, for greater durability. From an aesthetic point of view, the coulors reflect the conditions of the materials themselves.

The floors were levelled with debris from the demolished walls and finished with a hand-polished screed, exposed and finished only with a thin layer of wax. Wherever possible, the granite and slate walls were left visible. The existing wooden structure was replaced only where necessary, for safety reasons. An effort was made to keep everything that could be kept, adopting the option of “non-doing” as a methodological premise. In the living room, an existing tree trunk is the Alberto Carneiro we will never be able to afford. Both the existing wooden front door and the wooden window frames were restored, with no further interventions on the main street façade. Even the remnants of political posters pasted over the tiles during the April Revolution were preserved, as a form of material and intellectual heritage. Both the existing roof and the south façade were insulated for energy efficiency reasons. For the same reason, three new wooden frames were produced: painted bright red for protection and evocation, including shutters for privacy and light regulation. On the north façade, new interior wooden frames were added to create small winter gardens that help retain heat inside the house and keep street noise out.

The design choices we made (and those we didn’t) allowed us to achieve a budget of less than 500 euros/m2. For those willing to understand, this house can be read as following the guidelines of a manifesto yet to be written. A manifesto aimed at those living in so-called “developed” countries, and which can only be understood based on the following premise: (practically) everything we need is already here. Among voids and ruins, any wall is potentially a house, a school, a hospital, or a factory. It is up to us to reoccupy them, redistribute them, and reinvent them. Every piece of architecture is an unfinished utopia, as long as, to evoke Rossi’s words, we revive “politics as an option.”

In April 2023, this house received an honourable mention (2nd prize) in the first edition of the MGD Prize, awarded by the Portuguese Architects’ Association.